Vapor Where

by Farley Elliott

Stan Meyer is a college dropout from Grove City, Ohio. He was never a particularly thoughtful man, just one in a long line of hard workers who thought that with a little bit of ingenuity and a pair of strong hands, a man might be able to eke out a living. He worked, for a time, in any number of industries, including: roofing, welding, masonry, projectionist, door greeter, regional strong man, plumber and mechanic. With each job, a new set of skills that his hands had memorized, a new wrinkle in the brain where thoughts and ideas are stored.

After years of plugging things in, fueling things up or tossing out batteries, Meyer began to let his hands and brain-wrinkles work. Nights and weekends, Meyer would stay up for hours in his one-stall garage, bolting and fusing and scratching his head. Neighbors were hesitant to call the man a mad scientist, if only because they knew he didn’t have the foggiest idea what a scientist actually does. Instead, Meyer would click in and unplug and flip switches and sand down things until his fingers told his brain-wrinkles that it just felt right. For years, Stan Meyer figured that if he was sick of paying his electricity bill and getting gouged at the pump, someone else was too. And if there were enough someone else’s out there, and those someone else’s could find out about him and what he was trying to do in his one-stall garage in Grove City, he might be able to change the world.

The idea for Stan Meyer’s water-powered car is so simple, there’s no way a scientist could have ever come up with it. Instead of handwriting lines and lines of chalky equations on some college campus, Meyer thought that if he could just get an engine to run on water, there’d be no more need to bow down to corporations who control the energy faucet. After all, what is H2O but Hydrogen, a formidable energy outputter in its own right, and Oxygen, the biodynamic fuel that runs our daily lives. All he had to do what build a machine that could split that H and that O right down the middle. Use the Hydrogen as a clean, hyper-efficient fuel source and let the Oxygen runoff refuel the planet.

I too am from Grove City, Ohio, and just like Meyer I needed to find something to do with my time in a place where even the flies stand still in the summertime. Meyer was my father’s best friend; the two had bonded over a nudie magazine they found in the bushes at Darbydale Elementary in the 1950’s, and remained friends for decades thereafter. On weekends growing up, Meyer and my father and I would take to the Scolia River in search of bullhead and a few quiet hours. Sometimes, they’d pull out that tattered old porno, just to reminisce.

Around our house, Meyer would fix up a spent washing machine or unclog a toilet as if he owned the place. He was around our dinner table so often you’d have sworn he had his own key, which the man may well have carved himself. But eventually I grew older and found the thought of a neighborly middle-aged man dropping by my family’s house whenever he felt like it to be a bit uncomfortable. There was never any harm or ill intent in Meyer’s ways, but when you’re trying to sneak a high school girlfriend out of your bedroom at 4 A.M. and you tiptoe through the kitchen to find an adult male sitting in your breakfast nook, chewing on a dry bale of Shredded Wheat and flipping through a manual on carburetors, it’s time for something to change.

When my father died in 1978 from complications that arose during a standard gopher hole demolition, Meyer seemed to take the opportunity to move on. The two of us rarely spoke, and on growing occasions we would pass each other in the aisle of the local Aldi discount grocery chain, and neither would say a word. I moved to New York City to pursue a career in either long form journalism or breakdancing (whichever came first), and for all I knew Meyer was back in Grove City, taking apart radiators like an autistic kid. Then, in 1990, I saw the video.

The footage is blocky and flat, as if television in 1990 was still a relatively new medium. The anchors from Action 6 News, Tom Ryan and Gail Hogan with their perfectly quaffed blond manes, seemed genuinely excited about a local story that they hoped would pick up some steam. The piece centered around one man; a lanky, eccentric fella with a midwestern drawl and a dune buggy the he claimed could run solely on water. And there it was, in static glory, Stan Meyer twisting the gas cap to his modified buggy combustion engine, pouring in a gallon of water, and riding off with a jostle into the long Ohio horizon.

Exactly as anchors Tom Ryan and Gail Hogan would have hoped, the video quickly sprung up the local and regional news ladder, eventually landing in the lap of a producer for ABC News, which chose to air the segment nationally. Just like that, Stan Meyer was a star.

With talk of Pentagon interest and car manufacturers chomping at the bit to get a look at Meyer’s signature “water fuel cell”, I was riveted. From my dusty walk up apartment in Hell’s Kitchen, I would scour whatever newspapers I could find for word of Meyer and his improbable invention. Coming back from long late night breakdancing sessions near Columbus Circle, I would pile up all of the newspaper clippings I could find and scour each one for updates, turns of phrase that would indicate the new future of water-based engineering. Surely the future was at hand, and America’s dependence on foreign oil would be a thing of the past.

But within three months, the news dried up, and Stan Meyer had disappeared. Prior to his absence, newspaper reports had begun to drop in little tidbits about his growing mania; tales of Meyer showing up late to press events in his rickety old Datsun, the water-fired dune buggy nowhere in sight. He took to criticizing the petrol industry directly and would off-handedly refer to Judo-American imperialism in the automotive industry. Only one true scientific outlet — a young startup laboratory known then as Fluid Combine Industries — had ever actually come out in praise of the discovery. Everyone else was a skeptic.

Towards the end, Meyer had become so erratic, the only news blurbs I could find about him would come from the The African Encore, a sleepy East Village-based publication with no actual reporters on staff and a penchant for repurposing old hoaxes as fact. Twelve weeks after Stan Meyer changed the world, that’s exactly how the world had come to regard him: as a hoax.

Now, in 2013, I don’t breakdance much. I still have the old shell-top Adidas hanging in my closet and it’s hard for me to look at a piece of cardboard without getting nostalgic, but there’s no room in the street corner dance game to a middle-aged writer with a sticky hip. I’ve long since given up the dream of becoming the next Flashy Mike, Ashy Ron or BubbleBaby, the kings of street dance style when I was coming up. Now, I write about whatever the world sends me.

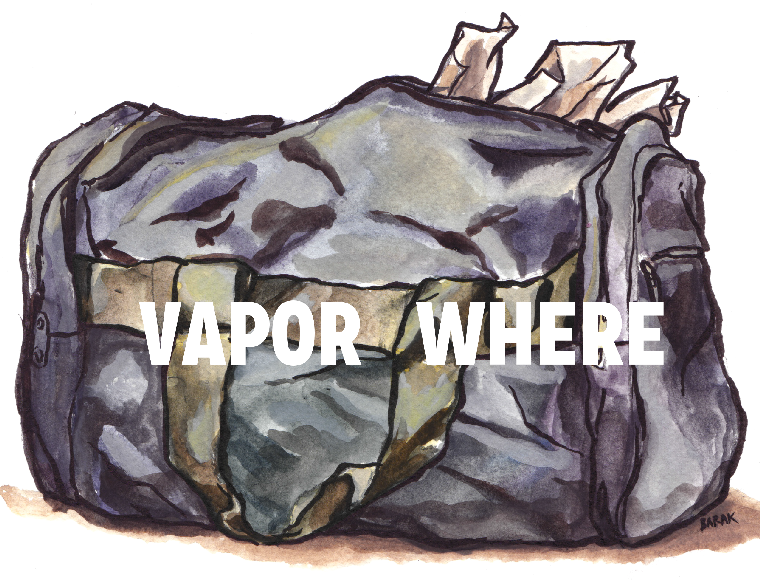

Bleary-faced and sporting a pronounced limp, Meyer knocked on my door at 11:30 P.M., carrying a duffel bag full of scattered papers. The first words he said to me were “It’s been a long time,” as he moved past and into the living room. He set the duffel bag on the floor and blacked out every window with garbage bags, explaining that he’d been watching my apartment for nearly a week. When I finally picked my jaw up off the floor long enough to ask where he’d been for 23 years, Meyer stated simply “in the headlines, but you just couldn’t see me”, then asked for a glass of water.

Whatever had happened to Stan Meyer, he was in a constantly rattled state. My phone would beep with the sounds of modern technology, and Meyer would twitch nervously in the direction of the sound, grabbing at the handles of his duffel bag. Unsure of what else to do with the disheveled man, I ordered up some Persian food from a menu that had been slipped under my door. It was a place I hadn’t heard of before, but I figured that getting something in our stomaches would help to settle us down.

Settle us down, indeed. After badly tipping the clean-shaven delivery man while Meyer tucked himself out of sight in a closet filled with my old breakdancing stuff, the two of us sat down to eat silently in my living room. He ate ravenously, like a man who couldn’t remember his last meal and wasn’t sure when the next one would be coming. Instead of fortifying ourselves for a night of intense conversation, the halal kebabs lured us into a much needed heavy sleep.

After what felt like days, I woke to find Meyer splayed out on my couch, clutching his duffel bag to his chest. Soon, he wrestled himself awake, and I made a pot of Folgers. Meyer began to recount to me the most fascinating tale of espionage, murder for hire and life on the run that I’ve ever heard. And after he had finished, I understood why he’d tracked me down in my studio apartment in Bushwick. I was literally the last person on Earth who could help Stan Meyer.

Within days of unveiling his water fuel cell on Action 6 News out of Columbus, Ohio, Stan Meyer was uneasy. The story had gained so much traction so fast (and why wouldn’t it, given the implications), that men in dark suits and sunglasses had begun knocking on his door at all hours of the day and night. Convinced that if he slept, the dune buggy would be pulled from his one-stall garage and disappear forever, Meyer took a chainsaw to the side of his ranch-style home and parked the thing in his living room. There he would sleep, handcuffed to the fuel cell with the rest of his body stretched out onto a sleeping pad and, for a pillow, a brand new duffel bag filled to the brim with his soon-to-be-filed patents.

First, it was the Pentagon that came calling. Nicely at first. A federal Defense official introduced himself to Meyer as Mr. Block, and began to inquire as to the nature of Meyer’s invention. Smiling and chatty, he happily poked through the ins and outs of the machinery with Mr. Block, who took copious notes and would cluck at the roof of his mouth at the slightest bit of design ingenuity. Mr. Block thanked Meyer profusely and promised to return with news from the Pentagon that might make him a very happy — and potentially wealthy — man.

After that came a Buick full of gas company executives. Men from Shell, SUNOCO and British Petroleum, walking lock step in grey wool suits despite the temperature. They were, naturally, a little more curt in their assessment of the buggy, but had to admit that the thing ran pretty damn smooth, and the only emission coming from the tailpipe was good old American oxygen. The men left frumpily, unsure of their next steps but desperate to know more about the water fuel cell that so naturally converted H2O into raw power.

In the dizzying weeks that followed, Meyer’s front lawn took a beating. Big city reporters crowded around his mailbox, hoping to catch a glimpse of the inventor at work. Meanwhile, vice presidents from Dupont, GE and Boeing would glide up onto the grass in black town cars and ask for a moment’s congress with Meyer, perhaps a demonstration or two. Often there were so many scientists and scholars at his door, from Fluid Combine Industries to MIT, that they had to wait in line. A neighbor boy would sell lemonade at an astonishing $1.25 a glass.

After that came the flood of state officials from the People’s Republic of China, from Russia and England, from Canada and France and Iceland, a nation overflowing with water and desperately in need of an economic boost. Each business tycoon and global head of state, in their turn, left Grove City with a very real fear: Stan Meyer may have changed the world, and he may not have our company’s or nation’s best interests at heart.

Little more than a month in, Meyer woke to find a masked man standing over him, trying to work the handcuffs loose from the water fuel cell as he slept. A short scuffle ensued, but when the harsh news camera lights flooded the room during the commotion, the intruder had vanished. That was perhaps the last night of real sleep Stan Meyer would get in thirteen years.

Convinced that one or more multinational entities were closing in on him, Meyer took to hiding the buggy in the back woods and hollers that dot the land around Grove City, showing up to press conferences in his trusty Datsun instead. But no matter what he said, people didn’t want to see the old man with the worn hands and his sloppy Datsun, they wanted to see the water-powered car.

And then something strange happened: the news turned on Stan Meyer. A false report of his eccentric anti-American car industry spouting had been passed around to various news wire services, and when combined with his increasingly edgy behavior, however justified, the media began to regard Meyer as little more than a lunatic with a good sales pitch. Soon enough, July 1990 would arrive and bring with it the reunification of East and West Germany. Suddenly, the news had bigger stories to cover, and when coupled with the U.S. invasion of Panama in January of that year, the rest of the world seemed a lot more important than Grove City, Ohio.

No one wanted to talk to Stan Meyer any more, but there were plenty of people who would be fine with stealing from him. Alone in his home, chained to his water fuel cell at night, Meyer began to realize how vulnerable he was. In the pre-dawn hours, Meyer slipped away. Whoever followed him would be close behind, always, and they might not have his best interests at heart.

1991

First, he tried the sand-whipped nation of Iraq. With a failing government and access to oil money, Meyer thought he might stand a chance of working out a business deal with a local tycoon to mass produce his water fuel cells for use in the harsh desert climate. After all, who better to understand the power of water than those arid civilizations who had relied on it for centuries? But soon after he arrived near the Kuwaiti border, Meyer began to notice that he was being followed. White men in large black SUVs had tracked him here, and were snooping around the village he had taken refuge inside.

Feeling threatened, Meyer decided to leave across the desert in the dead of night. His precious dune buggy and the water fuel cell that had put a target on his back were still hidden well away back on Ohio. All he had left were a duffel bag full of design pages and patent forms, those craggy hands and his brain-wrinkles. On January 17th, while trying to seek refuge in the city of Urfata on southwest Irag, he and his camel were fired upon by a man who looked suspiciously like Mr. Block, the man from the Department of Defense. The camel was fatally wounded and dropped to the ground, giving Meyer the chance to escape on foot with his duffel bag. In the mêlée a lone Iraqi boy was shot through the chest as he walked to morning prayer. Iraq news outlets called the shooting an act of war by American aggressors, and as Stan Meyer slipped north into Syria, the Unites States initiated Operation Desert Storm.

1994

Three years later, Meyer emerged in Detroit with an updated plan to take his patents directly to the biggest American car manufacturers. The idea was to mass produce his water fuel cell technology and make the United States a leader in clean, cheap energy. The results would pull the world out of poverty and save us all from letting the technology fall into the hands of the U.S. — or any — government, who could wield the power with unforeseen force. On his way to an initial meeting, Meyer (dressed in disguise as a tall, thin, androgynous person with a wig of black hair) was walking past Cobo Arena when he bent down to tie his shoe. Looking up, he saw a six foot madman approaching fast with a thick black club in one hand. Actings fast, Meyer ducked into a side hallway of the arena and sprinted towards the apparent ice rink at the end of the tunnel. Thinking better of the open space, at the last moment Meyer and his flowing black wig hid behind a drapery as the assailant ran past. A quick thud and a loud wail soon followed the assailant, and Meyer was able to sneak away through a laundry chute. It was only the next day, walking past a Radio Shack storefront, that Meyer learned the truth of the incident: after confusing Nancy Kerrigan for Meyer in his disguise, the assailant clubbed the rising figure skating star, dropping her to the ground. Realizing his mistake, the assailant reversed course and ran back through the arena, only to slip away in the back seat of a tinted Chrysler with tags that belonged to the GM Corporation.

1996

After the events in Iraq and Detroit, Meyer knew that the United States would provide him no safe haven. Still, with the summer Olympics being held in Atlanta, he saw no better opportunity to safely bring his peaceful invention to a foreign dignitary. Back-channel talks with Iceland had resulted in an agreed public meeting; Meyer would bring his duffel full of secrets, and Iceland would provide a national official to discuss the safe, constructive use of his water fuel cell. After sitting down on a bench beneath a sound tower inside bustling ALICE Park, Meyer looked down at his feet and noticed an exact replica of his duffel bag already sitting there. The features were an identical match, down to the black stitching and FarmAid patch that hung slightly off of one end. It was a setup.

Moving quickly, Meyer stood and began to take long strides away from the bench, shouldering through people wanting to see the headlining band Jack Mack and the Heart Attack. Within seconds, the replica bag tore open with the force of three pipe bombs, launching nails and ball bearings for two hundred feet in each direction. Shielded by the corner of a building, Meyer’s only wound was a nail that embedded itself inside his right calf, leaving him with the pronounced limp he came to my apartment with. CCTV footage of the man responsible for the blast show a tall, strapping, dark-haired man in an Icelandic track jacket, but in the aftermath of the bombing security guard Richard Jewell was wrongly fingered for the Centennial Olympic Park bombing in Atlanta. Years later, under mounting pressure from an ill-informed public, a staged arrest was made of a man by the name of Eric Rudolph, who looked similar to the Icelandic bomber.

1999

Holding out hope for some philanthropic backing, Meyer agreed to meet with John F. Kennedy Junior at Martha’s Vineyard. The cautious but charming Kennedy flew in with two scientists posing as his wife Carolyn and her sister Lauren Bessette. The group met at a rustic barn that the Kennedy family had owned for years, and for the first time Meyer believed he may have found a home for his water fuel cell. The Kennedy clan promised protection and the safeguarding of his idea. He was told that, with the Kennedy’s political connections worldwide, his invention could be used for good to promote the wellbeing of all global citizens. Meyer stayed behind at the Martha’s Vineyard compound as Kennedy and his undercover scientists were determined to reach New York by morning to begin preparations for the water fuel cell’s true media debut. Over open waters, his plane was incapacitated and crashed into the sea, killing John F. Kennedy Jr. and, for all the world knows, his wife and sister-in-law. Boeing, the manufacturer of the Kennedy aircraft, published a report of the crash and full details on the plane’s malfunction two hours before it actually takes place.

2004

After spending years on the run (“in the bush”, as Meyer would say repeatedly), he emerged in Thailand in late December 2004. The plan was to meet with Chinese officials offshore, in a boat that Meyer spent two years crafting himself. The intervening years made him cautious, and Meyer wasn’t about to board the boat of a foreign entity in international waters. Not if he ever wanted to make it home alive. After waiting just off shore near Ao Nang for nearly two hours, Meyer grew increasingly wary that the Chinese wouldn’t show, or worse, are waiting for his defenses to soften so they could strike.

Soon, a slow rumbling from beneath the boat turned into a maelstrom of sea waves and crushing futility, as Chinese-directed seismic activity along the ocean floor pushed trillions of gallons of water towards the Thailand shores in the worst tsunami in recorded history. Nearly 200,000 people were killed, while Meyer’s skillful craftsmanship allowed his boat to stay afloat long enough to reach the shoreline, where he was able to grab the fronds of a standing palm tree and wait out the water among the debris with his duffel bag. Eight years later, the movie The Impossible would be loosely based on this event in his life.

2009

Following China’s attempt to murder him and capture his secrets, Stan Meyer made his way to the Italian coast. He learned the native tongue and took a job fixing Fiats at a local auto mechanic shop. Needing to save some money and hoping to fall in with a group of fresh-minded individuals, Meyer accepted in a young American study abroad student to take over the second room him his quant Italian apartment. The woman, known to him as Amanda, was young and stunning. She seemed to never need to go to class, and instead became more interested in Meyer’s previous life and worldwide travails. Despite his being more than twice her age, the two fell hopelessly, romantically in love. They soaked in the sights of Perugia and the nearby countryside. Meyer took to drinking wine and staying up late with Amanda. For months, Meyer reported to his mechanic job with a smile on his face, and his Atlanta bombing limp even seemed to fade slightly. Eventually, over a plate of pasta at an al fresco café, Meyer came clean about his past: the water fuel cell, his time on the run and the many attempts at his life. “There is a duffel bag”, he said, “that outlines every detail of my invention. And it’s so dangerous that I can never tell you where it is, because some unknown demon might get you.The less you know, the better.”

Later that night, after falling asleep in her arms, Meyer woke up to Amanda and another unknown female at his bedside. The scene recalled his harrowing night with an intruder while chained to his beloved dune buggy back in Grove City, Ohio. The two women, believing Meyer to be still asleep, whisper in Italian of their plan to torture him until the duffel was recovered. Amanda, for her part, regretted that her affections hadn’t been enough to extract the needed information on behalf of the Italian government, but knew that the twelve-inch kitchen knife in her hands would be more than enough. Upon hearing that, Meyer jumped to his feet. In the struggle, the unknown female with Amanda was stabbed through the chest, blood pooling into the mattress and onto the floor.

After a tense standoff, Amanda with the knife and Meyer clutching the duffel that he’d pulled from the chimney flue, she fell into his arms and wept. Her job was simple: use her feminine wiles to win the mind of the uomo d’acqua, Stan Meyer, at any cost. But she hadn’t planned on actually falling for him. After all those hours spent holding each other in the Italian moonlight, she just couldn’t complete her mission. Not without tearing herself apart in the process.

As Meyer slipped out a back door and away down the cobblestone alley, the woman everyone knew as American exchange student Amanda Knox stood over the body of her unknown female associate, covered in blood. The sounds of Italian police sirens echoed closer and closer.

2012

After a few nomadic years among the tribesmen of Mongolia, learning their leather craft trade and better supplying himself for the harsh north Asian seasons, Meyer slipped into Russia in mid-2011 with hopes of joining one of the many movements that had bubbled up in opposition to the Russian government. Since Putin left power, there had been growing discontent in the Soviet, and Meyer believed that, perhaps like nowhere else, he could turn his invention over to forces of change that may help to bring freedom to the world in a way that existing regimes and global corporations would never dream of.

Once in Moscow, Meyer picked up a bootleg DVD copy of The Sopranos on a whim, and immediately became hooked. He spent the next three years catching up on the last two decades of television that he had missed. He really liked season two of The Wire, even though a lot of people thought it was the worst one. He gave up on Lost midway through season 4. “It just became really clear that they were making it up as they went along,” Meyer noted, although he’s currently really into VEEP.

The retelling of all these stories takes hours, sweating over the sort of details that would convince anyone that Stan Meyer is telling the truth. Plus, there’s a good 45 minutes where he just sat there, thinking silently about the sexual escapades that he and Italian informant Amanda Knox had. It occurs to me then that neither of us had seen sunlight for days, and walk over to the windows to remove the black trash bags that had been shielding us from prying eyes. I tug off the masking tape, and suddenly I feel like I’m floating. Instead of the apartment building across the street that has been my view for the past six years, there is nothing but darkness. I pull down the next black trash bag from its window frame, but still nothing. Meyer, sensing my panic, turns and stares into the empty blackness beyond my window panes. He whispers “what have you done”, but it’s too late.

Blinding light floods in through the windows — my windows — and the front door splinters under the weight of a combat boot. As body after body of armed personnel flood over me, I catch a glimpse of the world beyond what I had assumed was my front door. It is a warehouse. Somehow, my entire apartment has been duplicated to the finest detail, or transported and reassembled paint layer by paint layer. I cannot imagine the time involved in such a process, let alone how someone could possibly have gotten me inside this doppelgänger Bushwick walk up without actually walking me up any stairs. Then I remember the Persian food, with its catatonic qualities that left Meyer and I in a deep sleep. We had been drugged, and not with the runs that Persian food usually gives you.

With a boot on my throat, I croak out the requisite “what’s going on” question, but no one’s in a hurry to answer. Meyer, for his part, struggles mightily against two very tough-looking gun thugs in black fatigues as a third picks up his tattered duffel bag and hands it off to a stunning young brunette in a pantsuit. She looks up from the handoff, and I know that face: Amanda Knox.

With Meyer gagged and subdued and me face down on the carpeting, I can barely make out what’s happening. Knox moves towards Meyer and kisses him on the lips, slowly and passionately, but without a hint of the underlying emotion that Meyer had struggled with in his retelling of her portion of his tale. “I always knew we’d find ourselves together again”, Knox says as she continues to lean in close. “You’re upset about what happened in Italy in 2009, and I don’t blame you. But you’re really going to be mad at me when I tell you that I wasn’t even really working for the Italians. There are more important people that want your water fuel cell, Stan, and I’m here to give it to them. Now where is that dune buggy you’ve been hiding all these years?”

And in a flash of piercing neck pain, I’m gone. When I wake up, I’m back in my Bushwick walk up, and the view is exactly the same as it’s always been. There are no Persian food containers, and when I redial the number from my cell phone the restaurant’s line is disconnected. There’s no trace of Meyer, and if I hadn’t found that old nudie magazine under a couch cushion that he and my father used to jack it to, I’d be doubting my own sanity.

Stan Meyer is out there somewhere. Whether he’s alive, I can’t say. Why I’m still alive is anyone’s guess. Who took him, I won’t speculate (see above). But Meyer, that water-powered dune buggy and a duffel bag full of the sort of secrets that thousands have died for, they’re all very real. And whoever collects all three is going to be a very, very powerful person. ♦